In my previous columns I highlighted why the Bugatti Divo, the Hermès Birkin bag and even the world’s most expensive omelette are too cheap. What all of them have in common is the ability to create extreme customer value. Typical features are long waiting times and significant investment value. Birkins outperform almost any index. Pre-owned bags are significantly more expensive than new ones, reflecting the value in immediate availability.

The market for fine watches resembles this. The Swiss watch industry at large has had a catastrophic performance over the last three years, declining at a double-digit annual rate. There are few brands at the top that are able to create extreme value, while those that are relatively undefined “in the middle” have lost relevance at an unprecedented speed – they are unable to maintain attractiveness for millennial target groups who buy Apple Watches or go watchless; their business models are outdated; they have weak brand positioning; and they missed the boat in terms of digital mastery.

Few industries have been hit harder by rapidly shifting consumer preferences than watchmaking. Complacency in understanding the shift and resistance to embracing digital have amplified the pain for the mainstream-focused brands.

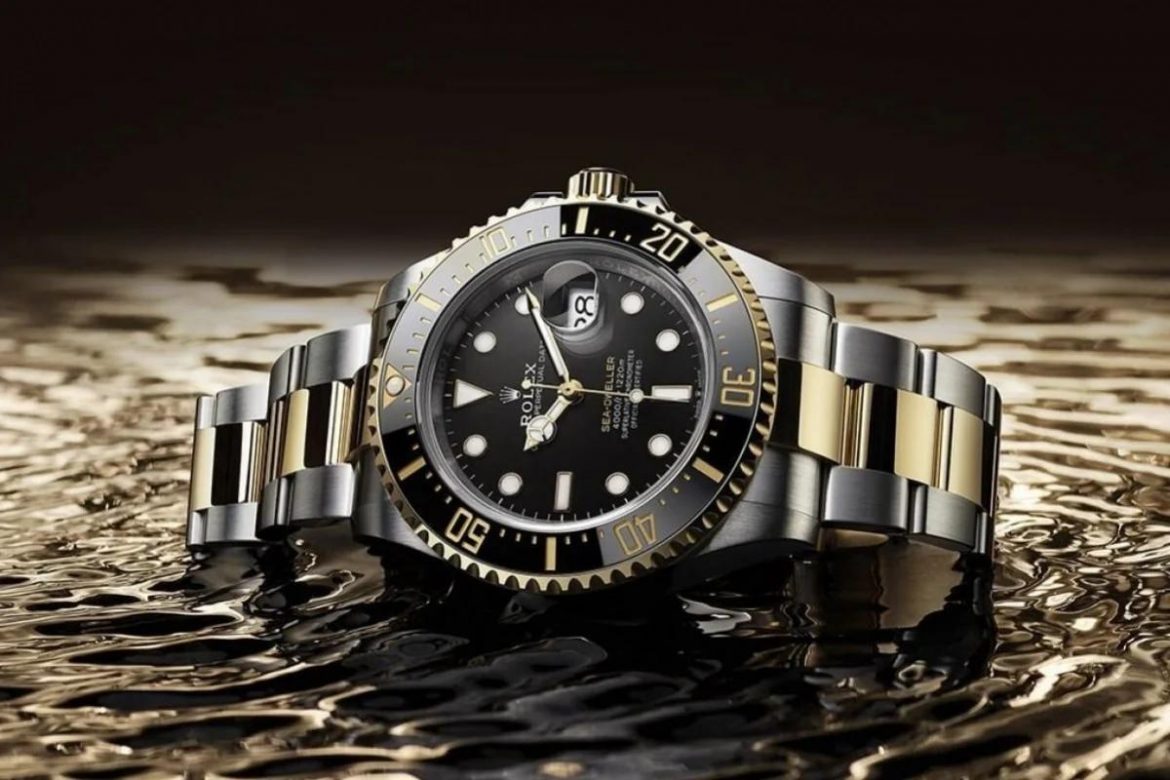

The picture is different at the top, where two brands are considered to be best-in-class: Rolex and Patek Philippe, alongside a few others like Audemars Piguet. They not only make great watches, they are also great marketers. When you ask people all over the world what is the ultimate expression of luxury, most will have Rolex top of mind. It’s a brand exuding prestige, timelessness and quality like no other, worn by those from industry tycoons to professional tennis players.

Similarly, Patek Philippe manages to convince customers that its watches are not simple purchases but part of a personal heritage, handed from generation to generation, the ultimate sign of achievement. I personally bought Patek’s Nautilus Annual Calendar and wearing it feels special every time the watch slips on my wrist.

Part of the allure is a strict limitation of the production of their collection. To get my Nautilus, I had to get on a waiting list as less than 10 of the specific model I ordered are assigned to the US annually. A positive side effect: while I frequently meet other Patek owners, I have never met anyone wearing the same watch. Keeping supply far beyond demand makes the ownership much more unique and leads to a significantly higher value than the price of the watch, which is high in absolute terms. However, as long as the value exceeds the price, these watches will be formidable investment objects.

Paul White, one of the leading watch experts and enthusiasts in the world, told me that “Rolex perfected the selective approach with the Daytona and frankly now on all Professional series (Submariners, Sea Dwellers etc), severely limiting production and distribution in the face of high demand. Curiously this strategy seems to be working even in what is a very unstable and changing luxury market right now.” In the end, luxury is all about extreme value creation.

In short: Patek and Rolex entice their customers by making the “consumption” more difficult through limiting the access to the objects of desire. The more people want them, the harder they are to get. While the brands which are undifferentiated “in the middle” collapse in terms of demand, the few brands at the top ride on a wave of lust, aspiration and strong limitation.

Note: This story was originally published on SCMP and has been republished on this website.