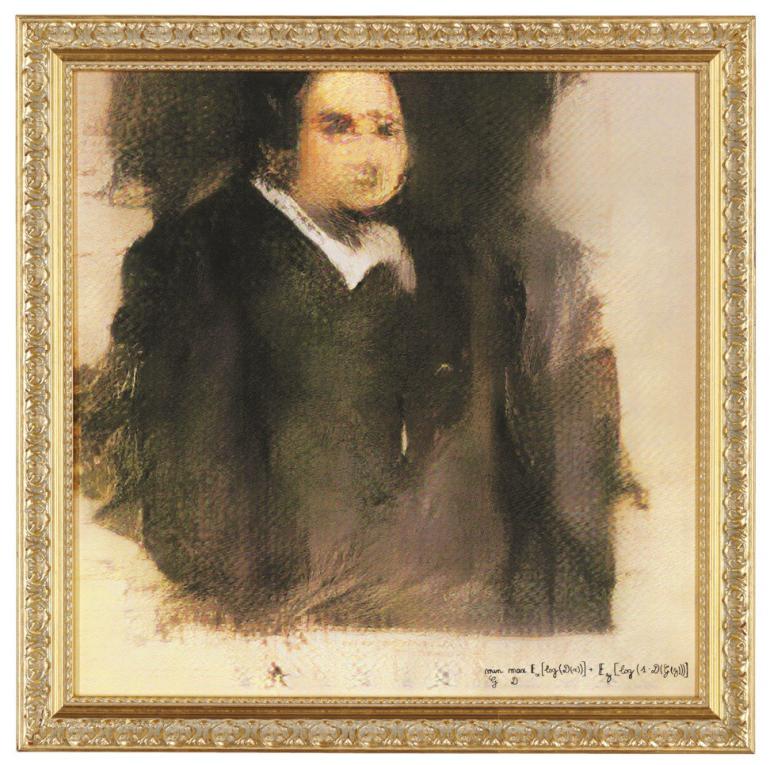

The portrait, ‘Edmond de Belamy’ – produced by three students – captured public imagination at auction last year, but some artists argue ‘it’s not art’

Edmond de Belamy, a blurry portrait of an aristocratic gentleman in a dark frock coat and white collar made the news when it was sold at Christie’s New York for US$432,500 ((HK$3.39 million) last October.

It was not the price that attracted attention – the sum is a mere sniff in the direction of the record-breaking US$91 million spent on Jeff Koon’s stainless steel rabbit inspired by a child’s inflatable toy – the highest price ever paid for work by a living artist.

What caused the commotion was that instead of an artist’s signature, there was an algorithm – the work was generated by artificial intelligence (AI).

Images generated using AI technology in Google’s pattern-finding software DeepDream have been circulating since 2015, but they have generally been appreciated for their science rather than art.

The guys behind this stunt are not even artists, but [members of] a very talented start-up, who knew how – with an initially false narrative, the right keywords and some good contacts – to cash in on the hype

– German artist Mario Klingemann

The Christie’s sale, however, was the first time one of the big players in the global art market shone a spotlight on the brave new world that challenges the boundaries of machine learning and creativity: AI art.

Like many other AI works, Edmond de Belamy was created using GAN – a generative adversarial network. Obvious, an arts collective comprising a trio of 25-year-old French students, fed AI with an algorithm and a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th and 20th centuries.

The algorithm is made up of two parts: the generator, which makes a new image based on the set; and the discriminator, which, Turing test-style, aims to tell the difference between a human-made image and one created by the generator.

The generator learns from its mistakes; when the discriminator is fooled into thinking that a new image is a real-life portrait, the result is something along the lines of Edmond de Belamy.

People are interested in AI art because it looks like what we know as art, but this is not art, this is just reproduction, just imitation. If a human was to make this art now, we would say it was bad art, so why is it interesting if a machine makes it?

– Maurice Benayoun, professor, School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong

The auction went on to capture public imagination, but not everyone was impressed, particularly other artists working within the field, who criticised the sale.

“The guys behind this stunt are not even artists, but a very talented start-up, who knew how – with an initially false narrative, the right keywords and some good contacts – to cash in on the hype,” German artist Mario Klingemann, one of the first creative coders to experiment with AI and art, says.

“I was disappointed that a marketing ploy as obvious as this actually worked.”

Klingemann’s own artwork, Memories of Passersby I, uses neural networks – what he calls “neurography” – to generate an infinite stream of imaginary portraits that are projected onto a two-screen installation.

Other versions followed. Memories of Passersby I was sold in March by Sotheby’s London for a much cooler US$51,000 with fees.

Robbie Barratt, a 19-year-old pioneer of GAN art, whose algorithms shared online via open-source licence were tweaked by Obvious for its project, has also reacted to the sale, describing Belamy as neither interesting nor original.

GANs are, by their nature, derivative: they don’t create, they generate.

Now a cornerstone of contemporary machine learning, GANs were first designed by researcher Ian Goodfellow in 2014.

Unlike the repetitious results produced by DeepDream, GANs can be trained to produce new and different images. But the images are still emulative and this, many agree, excludes them from serious consideration as art.

“People are interested in AI art because it looks like what we know as art, but this is not art, this is just reproduction, just imitation,” Maurice Benayoun, a professor at School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong, says.

“If a human was to make this art now, we would say it was bad art, so why is it interesting if a machine makes it?”

Art is about ideas; whether an artist uses a paint brush or AI, these are tools to communicate ideas. So while GANs themselves may not produce what many would consider as art, in the hands of an artist, they could indeed be used to speak of the world beyond the image.

“I’m not a painter,” says Klingemann. “My way of expression is through code. From my perspective, code allows me to translate what is in my head out into the world better than anything I could ever accomplish with my hands and physical tools.

“For me, personally, there is no question that what I and other serious artists in this field are creating with AI is art – and many curators, collectors and critics seem to agree.”

Klingemann is creatively involved throughout the art-making process, from the initial concept for a work, through selecting and modifying neural architectures, finding and curating data to train the models, combining various models and embedding them in other algorithms and, finally, choreographing and curating their output.

“AI in its current state is surprising, unpredictable and can be very inspiring but it’s still me who plays the creative role in this relationship,” he says.

I’m not a painter. My way of expression is through code [which] allows me to translate what is in my head out into the world better than anything I could ever accomplish with my hands and physical tools

– Mario Klingemann

A professor at Rutgers University in the United States has complicated the debate, however.

Ahmed Elgammal believes that GAN – think GAN 2.0 – puts creativity firmly in the capabilities of machine intelligence.

“GAN tries to emulate images, but art must make something new. So we developed our creative adversarial network,” says Elgammal, a professor of computer science and director at Rutgers’ Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, which created a program called AICAN (Artificial Intelligence Creative Adversarial Network).

Elgammal fed the program with images from across five centuries, from the Renaissance to the present day, all grouped into categories by aesthetic, so that it could learn the concept of style.

Like in GAN, AICAN was tasked with learning the aesthetics of existing works of art, but it was not allowed to closely emulate styles. This effectively gave the machine two opposing forces: follow the aesthetics, don’t repeat styles.

Much of GAN’s art is abstract; Elgammal suggests this is perhaps because the algorithm has grasped that if it wants to make something novel, it cannot go back and produce figurative works as existed before the 20th century.

The AICAN artwork Divided Sunshine (2018), a pigment print on rag paper, is a field of blue over a hazy strip of white, reminiscent of the sky. A thick streak of deep red runs vertically down the centre of the image, alongside a thinner, incomplete strip, also red.

It was exhibited at SCOPE Miami Beach and The Arts+ in Frankfurt last year.

“The definition of creativity is a long and ongoing debate,” Elgammal says. “Immanuel Kant’s definition of the 18th century is based on two qualities: something has to be novel, and it has to have influence, like Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [1907], which sparked the cubist movement. This definition helped inspire GAN.”

For me, personally, there is no question that what I and other serious artists in this field are creating with AI is art … it’s still me who plays the creative role in this relationship … and many curators, collectors and critics seem to agree

– Mario Klingemann

“But the division of art and science – aesthetics as subjective and science as objective – can also be traced back to Kant, and I don’t believe this is true. I established this lab because I believe looking at art will advance AI.

“Intelligence is not just used in driving a car or playing chess, it is involved in listening to music, comprehending literature and enjoying art. If we want to build a machine that is intelligent, we need to step into this territory of creativity.”

Elgammal has conducted tests with viewers – flesh-and-blood discriminators – to assess reactions to works by humans and machines. He says there is very little difference; in fact, some people are more inspired by machine-generated art.

Does this suggest GAN works should be considered art? Not if your definition of art is that it should speak of the wider world or provide an emotional response to it. For the time being, AI art remains in the realm of science fiction.

This is not what art is about

Many see the extravagant US$432,500 paid last year for the world’s first AI art at auction as indicative of the art market in general.

Klingemann, who describes Edmond de Belamy as “mediocre and unrepresentative”, says the sale “tells you more about the art market than about art”.

Like Klingemann, Benayoun is frustrated with the fetishisation of art. A market in which an unnamed buyer spends US$91 million on Koons’ stainless steel sculpture of a rabbit is one that inspires incredulity.

“The art market is important, of course, but who is inspired by this rabbit?” asks Benayoun, who has been described as France’s most cutting-edge artist.

The art market is important, of course, but who is inspired by this rabbit? The technique of making a rabbit of steel or imitations of paintings made of bits … This is not what art is about

– Maurice Benayoun

“The technique of making a rabbit of steel or imitations of paintings made of bits … This is not what art is about.

“When someone invests US$91 million, I hope they will invest US$92 million in artist Piero Manzoni’s 1960s work Artist’s Shit – literally his own excrement in a can. This is a better artwork, was done long before, and it’s organic.

“I hope whoever bought the rabbit will go bankrupt very soon as there are so many more relevant ways to spend this money. Art is supposed to help us understand the world and perhaps change it a little. Art is giving shape to ideas.”

Benayoun is literally giving shape to ideas through a blockchain-based art project called Value of Va lues (VoV).

In an attempt to find the real, economic value of human values through EEG (electroencephalography), an interactive art installation titled Brain Factory allows the audience to give a shape to abstract concepts through Brain-Computer Interaction (BCI), and then converts the resulting forms into physical objects.

“I hope whoever bought [Jeff Koons’] rabbit will go bankrupt very soon as there are so many more relevant ways to spend this money. Art is supposed to help us understand the world and perhaps change it a little. Art is giving shape to ideas”

– Maurice Benayoun

So anyone sitting in the artist’s chair can, merely by thinking of an abstract concept like justice, power or peace, can “design” them in 3D model form.

The neuro-designed shapes are entered onto the blockchain and can be converted into cryptocurrency, giving a monetary value to the art. If thousands of the shapes are bartered or sold, all tracked in real time, this gives metaphorical insight into the relative value of human values and the workings of the art market.

Yet projects such as VoV, and the fact that AI is able to create infinite variations around a concept or style, showing that the idea of a single perfect work is merely a dream, may be no match for the way in which the single artefact, the unique object, is revered today in an almost cultish fashion.

“Art is a belief system, like a religion in which rationality has no place, so I doubt that the notion of art objects as fetishes that have arbitrary high values will go away any time soon,” Klingemann says.

Note – This story was originally published on SCMP and has been republished on this website